The late-November 2025 breach of Upbit, the largest South Korean virtual asset exchange, Upbit, has quickly become one of the most scrutinised crypto incidents of 2025. Not only because of the scale of the theft - with roughly $30-37 million stolen, but because of the immediate question that always follows with thefts of this size:

Was this another Lazarus Group operation?

South Korean regulators, blockchain investigators, and global intelligence analysts are all examining the evidence - but the picture remains complete.

While we at NOMINIS continue to the efforts to uncover the thieves, this article will examine the evidence that is publicly confirmed at the time of writing, consider why some experts believe North Korea could be involved, why attribution remains uncertain, and how the attack is already reshaping South Korea’s approach to crypto regulation and compliance.

What Happened?

On 27th November 2025, Upbit suffered an unauthorised withdrawal from one of its hot wallets, resulting in the loss of roughly $30-37 million worth of assets. The stolen funds were moved rapidly across wallets, split into smaller batches and routed through various blockchain networks. This kind of immediate fragmentation and cross-chain movement is typical of professional laundering operations.

Upbit responded by suspending deposits and withdrawals for the affected network, isolating remaining funds by transferring them to cold storage, and assuring customers that losses would be covered.

Investigators and external researchers later pointed to a potential weakness in Upbit’s signature-generation process, suggesting that predictable signing data may have allowed private keys to be reconstructed. Although this theory fits the observed behaviour we know to be confirmed, this has not been confirmed as the definitive cause.

What is certain is that the attacker exploited something around the blockchain, rather than the blockchain itself - an increasingly common pattern among many attacking bodies across scams and hacks in 2025.

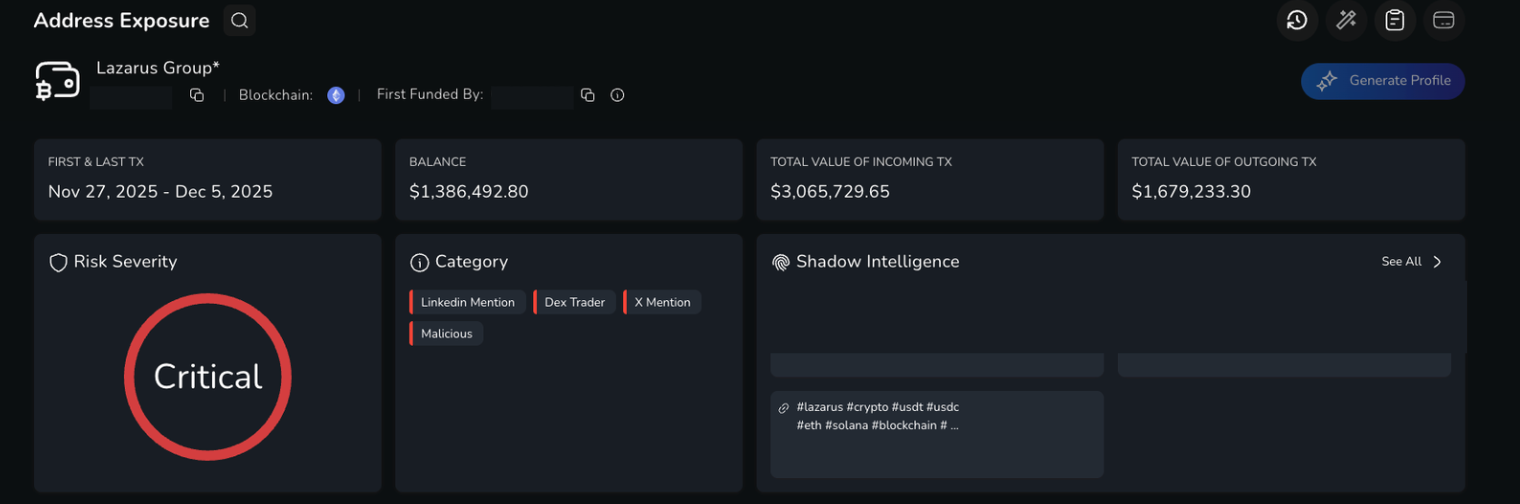

Analysis of one of the attacking wallets involved in the Upbit Breach, currently labelled as Lazarus Group. This is subject to change as further evidence emerges.

Why do some believe it was North Korea’s Lazarus Group?

Who is the Lazarus Group?

“Lazarus Group” is a collective label, used by international security agencies to describe multiple DPRK-linked cyber units, responsible for some of the largest digital thefts in history. These groups operate with state direction, blending espionage, financial crime, and sanctions evasion. They are disciplined, persistent and tend to reuse the same laundering pipelines and infrastructure families across operations, although have been known to widen their targets from just exchanges to also target high-asset individuals too.

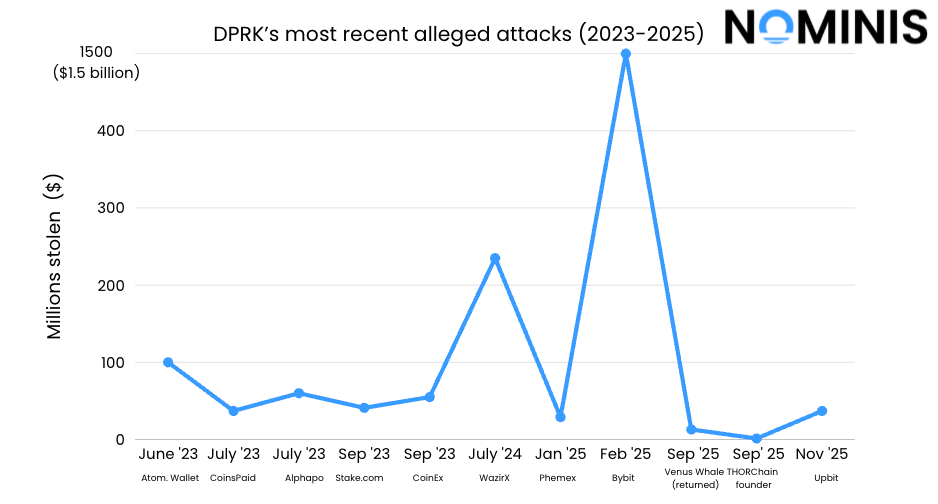

The motive behind Lazarus Group’s attacks is well-documented. Stolen crypto is converted into resources for the North Korean state, including funding for weapon development, ballistic missiles programs, and sanctioned procurement networks.. US Treasury and allied intelligence reports consistently describe DPRK cyber thefts as proliferation financing. In this context, crypto thefts are not just profit driven, but are geopolitical, with concerning real world consequences, presenting grave threats, according to academics. Further information about the nature of Proliferation Financing can be found in a deep dive article here.

The indicators pointing towards the DPRK

Some elements of the Upbit breach align closely with Lazarus Group’s historical behaviour.

Firstly, the geopolitical interests of the Lazarus Group, as an attacking team state-sponsored by North Korea, makes Upbit a suitable target. Being the largest South Korean crypto exchange, it sits at the intersection between political rivalry and high-value financial infrastructure - an attractive combination for a group seeking both funds and strategic disruption. In fact, the Lazarus Group previously hacked Upbit, in 2019, for $41 million.

Secondly , the choice of target fits a well-established pattern. Lazarus has repeatedly struck centralised exchanges with large use bases and high on-chain liquidity, for example Coincheck in 2018, KuCoin in 2020, WazirX in 2024 and Bybit earlier in 2025. Upbit sits firmly within this category: a major exchange with substantial hot-wallet exposure and the ability to move large sums quickly. These characteristics have consistently made CEXs particularly attractive to DPRK-linked actors looking for high-yield, fast exit opportunities.

The suspected attack vector also mirrors Lazarus’ operational style. Although no final root cause has been confirmed, the unauthorized withdrawals appear consistent with some form of credential compromise, administrative impersonation, or access-level abuse within Upbit’s infrastructure. Lazarus operations have long relied on social engineering, spear-phishing, credential theft, and infiltration of internal systems rather than purely on–chain exploits. This blend of human-layer intrusion and privileged-access compromise is one of Lazarus’ signature moves.

The laundering behaviour further strengthens the comparison. The stolen funds were dispersed at high-speed, split into multiple wallets, and moved across networks almost immediately: a pattern that blockchain analytics firms frequently flag as ‘Lazarus-like’. Their laundering playbook depends on rapid movement, fragmentation, and early obfuscation to get ahead of blocklist coordination. The Upbit flows tracked closely with this established rhythm, showing the same urgency and operational tempo used in previous DPRK-linked thefts.

Timing also plays a role. Lazarus attacks often occur in clusters and frequently align with periods of increased geopolitical or economic pressure on North Korea. The Upbit breach arrived several months after the record-breaking Bybit exploitation, suggesting a continued need to replenish foreign-currency reserves. Late-2025 fits the broader cadence of Lazarus activity: sustained, opportunity and globally distributed.

Why We Cannot Be Certain: Attribution Gaps

Even though the Upbit breach echoes many Lazarus Hallmarks, meaningful gaps remain, and they prevent investigators from making a definitive attribution.

To begin with, the scale of the attack diverges from Lazarus’ recent behaviour. The theft amounted to between $30-37 million., a significant amount, but modest compared to Lazarus’ blockbuster operations, which routinely exceed hundreds of millions, and occasionally reach the billion-dollar mark, in the case of the Bybit hack. In fairness however, the Lazarus group previously hacked Upbit for $41 million, a similar target. This could suggest the attack was a more opportunistic hit, to probe the defences of the exchange. It could also mean something even simpler - a group unrelated to Lazarus, but mimicking their style or previous target, which would relate to the Group’s recent behavior, focusing on lower-profile intrusions of high-asset individuals with lower level security compared to an exchange.

The technical nature of the breach also complicates attribution. Unlike many of Lazarus’ most sophisticated exploits, cross-chain bridge compromises, validator takeovers, or protocol-logic bypasses, the Upbit attack appears to have occurred entirely within a centralised exchange environment. There was no smart-contact exploit, no bridge compromise, and no on-chain manipulation. Instead, the evidence points towards a credential -level intrusion, a simpler but highly effective attack vector which proved effective for DPRK’s suspected attacks on THorChaIn founder, JP, for example. This attack vector is not exclusive to Lazarus, many cybercriminal groups rely on similar methods, confusing attribution.

Equally important is that no malware, phishing infrastructure, or other classic Lazarus artefacts have been publicly reported. Typically, Lazarus leaves behind at least some traces of their tooling: malicious documents, phishing domains, malware loaders, or command-and-control infrastructure. As of now, none of these fingerprints have been confirmed in the Upbit case. Their absence does not rule our DPRK involvement, however, as sophisticated attackers are increasingly careful about their operational security, but it weakens the confidence of attribution.

Another subtle deviation is the choice of assets. The attacker drained primarily Solana-ecosystem tokens, which historically have not been Lazarus’ primary preference. Their laundering has traditionally flowed through ETH, BTC, Tron and wrapped assets. That said, Solana’s explosive growth in liquidity and its speed for high-velocity transfers make it an attractive modern laundering option. This deviation could therefore reflect adaptation of the Group’s methodology, rather than a new actor.

All these points form a nuanced picture : the Upbit attack strongly resembles Lazarus tradecraft, but not strongly enough to confirm it.

The Broader Problem: Why Attribution is Difficult

Attributing a blockchain-based attack to a specific state, organisation or individual is extremely difficult, for several structural reasons:

On-chain behaviour is fundamentally pseudonymous. While on-chain transactions are always recorded, wallet addresses do not inherently reveal ownership, intent or identity behind such transactions.

Different attacking actors often copy each other’s tactics. High-performing laundering techniques and exploit patterns get replicated across the entire ecosystem.

Attackers actively disguise tracks. Mixers, cross-chain bridges, peel-chains and liquidity-splitting make it nearly impossible to link activity to a single actor without off-chain intelligence. For DPRK-backed groups, there may be even greater caution in obscuring tracks, to prevent allied nations from recognising that North Korea is acquiring additional funds.

Attribution requires multiple disciplines. Blockchain forensics alone is rarely enough: investigators need malware analysis, OSINT, intelligence sharing, and often law enforcement access to infrastructure logs to make an assertive assessment.

Therefore, even when an attack looks like a Lazarus operation, similarity is not proof.

Why Premature Attribution is Dangerous

Jumping to conclusions carry real risks: for exchanges, regulators and the wider compliance system.

Misattributing an attack could mislead investigators, causing them to overlook the real perpetrator. It can distort regulatory responses, pushing policymakers towards assumptions rather than real evidence. It can also create further unnecessary geopolitical tension, without proper grounds for accusations.

Ultimately for compliance teams, while a theft is a theft, misattribution can lead to faulty risk assessments, impacting transaction monitoring, risk screening, and appropriate incident response.

For all these reasons, the safest and most responsible approach is to remain evidence-led, rather than assumption led. A case could be “Lazarus-like”, but until multiple indicators converge, both on-chain and off-chain, attribution should remain probabilistic, rather than declarative.

NOMINIS Unique Insights

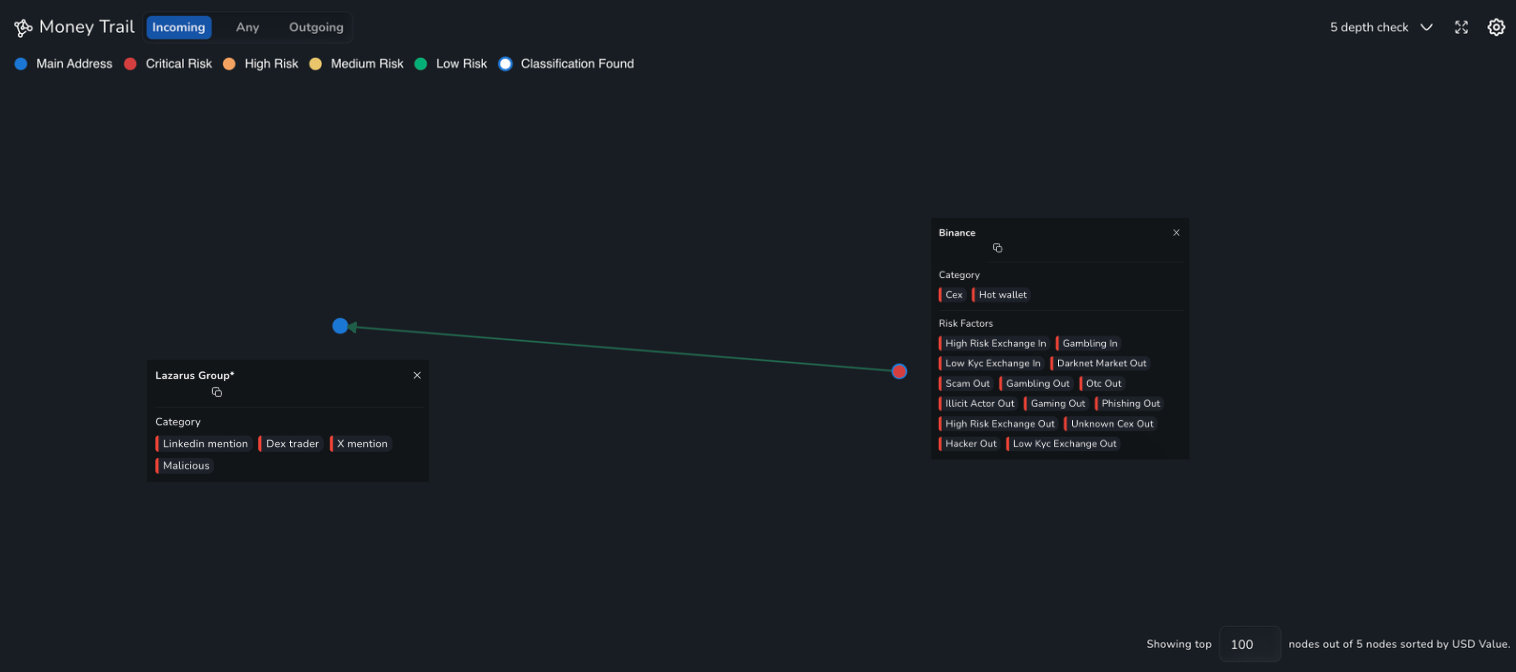

Using the Money Trail feature available on the NOMINIS Transaction Monitoring platform, NOMINIS can exclusively reveal relationships between the wallets suspected to be Lazarus Group, and Binance, the largest centralised exchange globally. In fact, in the particular case below, a Binance wallet address was the first to fund the wallet suspected to belong to Lazarus Group.

While this does not, on its own, confirm whether Lazarus Group did in fact commit the Upbit attack, it establishes a verifiable and noteworthy on-chain fact. The wallet that committed the Upbit attack, whether belonging to Lazarus Group or not, was first funded by Binance.

This observation is particularly significant in light of Binance’s ongoing legal scrutiny, including allegations related to failures in preventing terror financing and the provision of infrastructure that enabled known high-risk or sanctioned actors to operate. Although Binance could not have foreseen that this wallet would later be used in a major exchange attack, the on-chain evidence reinforces broader concerns around Binance’s historical shortcomings in detecting and mitigating high-risk wallet activity at the point of entry into the crypto ecosystem.

As enforcement actions and regulatory expectations continue to intensify, this case raises a critical question: whether Binance will implement substantive, proactive controls to prevent its platform from being used as an initial funding source for hackers and other high risk actors in the future.

Concluding Thoughts

The Upbit breach exhibits many of the behavioural, strategic and operational hallmarks historically associated with North Korea’s Lazarus Group. The choice of target, the laundering velocity, and the broader geopolitical context all make DPRK involvement a credible and serious hypothesis. However, credible does not mean conclusive.

At present, the publicly available evidence supports a Lazarus-like assessment rather than a definitive attribution. Key technical artefacts remain absent, the attack vector is not unique to DPRK-linked actors, and the on-chain indicators alone are insufficient to assign responsibility with certainty. This ambiguity is not a failure of investigation, but a reflection of the modern reality of crypto crime, where sophisticated actors deliberately blur attribution lines.

What the Upbit hack does make clear, is a deeper structural issue. Large-scale exchange compromises continue to exploit off-chain weaknesses, while the initial funding and laundering of attackers still frequently pass through major centralised platforms. The on-chain link between the attacker wallet and Binance underscores the urgent need for stronger entry-point controls, earlier risk detection, and pro-active transaction monitoring across the industry.

A combination of Shadow Intelligence and wallet clustering has led the NOMINIS Transaction Monitoring system to currently label the attacking wallets that performed the Upbit attack, as Lazarus Group. While this is subject to change as we gather more information and evidence, it should be noted that regardless of the label as Lazarus Group or otherwise,, the risk level of this wallet remains critical. Coming into contact with a wallet known to commit the Upbit hack is detrimental, and should be avoided. Correct procedure according to AML/CTF frameworks would be to perform a Suspicious Activity Report, to prevent others coming into contact with critical risk level wallets.

Whether or not Lazarus ultimately proves responsible, the lessons remain the same. Attribution must be evidence-led, not assumption driven, and compliance frameworks must evolve to address not just who carried out an attack, but how high-risk actors are able to enter, move, and exit the crypto ecosystem at scale.